Who was Daisy Gordon?

Daisy Gordon has arguably been the most significant influence on girls in the USA ever. The founder of the Girl Scouts of America, an organization which has grown from 18 girls to over 3.7 million today, Daisy and her organization has impacted more than 50 million girls, women (and even a few men) who have belonged to it.

Born Juliette Magill Kinzie Gordon on 31 October 1860, in Savannah, Georgia, she was the second of six children of William Washington Gordon and Eleanor Kinzie Gordon. Her paternal line is traced back as far as John Gordon & Janet Ogilvie of Pitlurg, Aberdeenshire, Scotland (about 1520.) Daisy’s line descends from their son John and his wife Isabel Forbes. Isabel Forbes is a Gordon descendant, on her paternal line, of William Forbes (1452) and his wife Christine Gordon. Christine was the daughter of Alexander Seaton Gordon and Elizabeth Crichton, and thus through his mother back to the progenitor of the Clan Gordon, Adam de Gordon!

Her brother Arthur best summed up his “brilliant eccentric” sister, “…she was so many-sided and unexpected and incalculable. There was nothing conventional or tepid or neutral about her. She had an eager desire to realize life to its utmost, and she would try anything, particularly if she had never attempted it before. What she enjoyed, she enjoyed to her very finger tips; and one reason why she was so eagerly sought after lay in the fact that she was not only very entertaining and amusing when she desired to be, but she was frequently killingly funny when she had no intention of being funny at all.”

As a young girl, Daisy was fond of exotic birds, dogs, and the arts. She formed clubs, invented games, rode horses, played tennis, wrote poetry, wrote and acted in plays, and she created a children’s magazine that lasted for five years. One of the clubs that she formed was called the “Helpful Hands,” it was a sewing club with the purpose of making useful items for the poor. She was known for her sense of humor and loved a good practical joke. She was known for bringing home strays of all kinds. She showed her bent for the humane treatment of animals in her confession that “sometimes they weren’t strays, but I felt that their owners were neglecting them.” This enthusiasm was sometimes taken to extremes in her youth as she tells us in the Thanksgiving turkey incident!

“When I was little, people fattened and then slaughtered their own Thanksgiving turkeys. Just before they cut off our turkey’s head, I convinced my family that brutal decapitation was inhuman. I argued that he could be chloroformed first, and then wouldn’t feel anything. They finally gave in and agreed to do just that. Then they plucked the turkey and put him in the icebox. When they opened the icebox the next day, the bird was wide awake and bolted out of his frozen “cage.” The cook, thinking the bird had been dead, became hysterical and jumped up on top of the stove!”

She loved the arts and studied poetry, learned to sketch, and eventually became an accomplished sculptor and painter.

As a young girl she attended the school of Miss Lucille Blois in Savannah, just around the corner from home. She struggled in arithmetic and spelling, but was overall an able student. In 1873 she and her sister, Eleanor, were sent to boarding school at Virginia Female Institute in Staunton, Virginia. She spent three years at VFI (now known as Stuart Hall) before attending Edge Hill in Albemarle run by Misses Sarah and Carrie Randolph, and finally attending Mesdemoiselles Charbonnier’s, a French Finishing School in New York City. According to the Stuart Hall website the courses were divided into separate schools in what is known as the “University of Virginia plan.” A diploma and a medal were given for each subject exam passed. The rules of conduct at VFI were strictly enforced, and even though it was against the rules to read novels, Daisy seems to have found pleasure in doing just that, much to her mother’s chagrin. Nellie Gordon wrote her daughter “How came you to ever begin such a book as Hester Morely’s Promise! No! You cannot finish it and I am very vexed that you ever got hold of it. You may read Lorna Doone if you like, but I don’t think you will enjoy it. Kate Coventry and Jessie Trim I know nothing about and you can’t read them until I do…” Nellie did approve of the great English poets and novelists and did give Daisy permission to read from Shakespeare, Scott, Thackeray and Dickens as she pleased.

In one letter home from VFI, Daisy tells of a funeral that the girls held for a poor frozen robin they had found. Daisy made a coffin out of an old pasteboard box with pin heads as decoration on the lid to simulate nail heads, and she made a shroud and cap for it and laid it out on her doll bed. The service, with Daisy as the parson, was held in the schoolroom complete with six girls acting as pall bearers, and another girl, Sally, as chief mourner, who “wept and tore her hair and acted just like a chief mourner.” The Death of Cock Robin was recited, and the girls sang “The North Wind Doth Blow and We Shall Have Snow,” Daisy goes on to tell how the girls all stood in two rows “teachers included and went two by two to the grave.” Miss Kate had even given them permission to have an English Service in honor of Cock Robin, and a real marble stone for the marker upon which they wrote “Here lies Cock Robin Snug as a Bug in a Rug.” It is easy to see Daisy’s love of animals and flair for the dramatic. The fact that she was able to involve the whole school, teachers as well, shows how persuasive she could be, a trait that stood her in good stead throughout her life.

She did well academically earning medals in English, French, piano, elocution and drawing. Apparently she had wanted the medals engraved with her nickname Daisy, (she was never called anything but Daisy by all who knew her) but the school refused. To add insult to injury her first name was misspelled and her name was engraved as Juliete Magill Gordon!

At sixteen, Daisy was at Edge Hill School in Albemarle, Virginia run by the Misses Sarah and Carrie Randolph, great-granddaughters of Thomas Jefferson. Being a typical teenager, she seems to have been testing the waters of independence a bit when she wrote home reminding her mother that even she had been a bit of a handful. She writes, “Mama, I can’t keep all the rules, I’m too much like you. Imagine yourself when at school, on being asked to do something against the rules in order to have some fun, clasping your hands across your bosom and saying, ‘How wrong!’ I’ll keep the rule about studying after the light bell rings, about getting up in the morning too soon and I’ll keep clear of the big scrapes but little ones I can’t avoid.” (Of course her mother had met her father when on a visit to Yale she slid down the banister and landed right on top of Willie Gordon! So Daisy was sure her mother would understand, and her father would chuckle.) On her graduation she was crushed when she didn’t get the scholastic medal she had worked so hard for and expected. She wrote home to her mother that it was “against the principals of this school to give two medals to one girl (an unheard of thing) so as the drawing medal was a higher honor I suppose Miss Sarah thought I would rather have it. But I would not. For Papa told me in his first letter to work hard on everything but drawing and now he won’t think I did!”

At Charbonnier’s the girls were immersed in French, not being allowed to speak anything else. She seemed to be proud of her academic prowess in the language, especially in spelling and grammar having received top scores. Since spelling had always been a problem for her, she proudly wrote home that “this explains it all – my faculty of spelling being singularly small, has been absorbed in French Dictées!” Her pride in her accomplishments only lasted until her next letter from home when her then seven year old brother, Arthur (whose governess was French) advised Daisy not to write home in French as she could not spell in French either. Daisy added the skill of painting in oils to her artistic training, and attended dancing classes at Dodsworth’s Dancing School. Charbonnier’s was strict and she poked fun at the excessive formality as well as at the dancing classes, but still managed somehow to not even get into “little scrapes.”

Following her debut in Savannah Society, she traveled extensively throughout the United States and Europe. In 1884, she made her second trip to Europe, and this time visited Scotland with the Carters, friends from Charbonnier’s. She was quite taken with the beauty of Scotland and wrote “The Mountain pass of Trossachs is enough to make one thank God for being alive and that there are such beautiful things on earth. Strange to say, I had a patriotic feeling as if I was a Scot myself in some distant way, and I don’t care if Papa does chaff and say we were probably servants and yeomen of the Gordon clan when our ancestors were in Scotland.” The irony of this statement, given her pedigree back to the progenitor of the clan, is exquisite and yet her feeling of patriotism for Scotland is an all too recognizable one which many a Scotsman has experienced.

Daisy suffered from chronic ear infections as she grew up. Always one who stressed personal responsibility, she wrote that “I had a series of ear infections and was losing patience with ‘traditional’ medicine. I had heard that silver nitrate was the ‘newest’ treatment, and I insisted that the doctor use it on me. Unfortunately, it was too powerful a mixture, and it caused me to go deaf in that ear.” At her wedding in December 1886, to William Mackay Low (Billow to the family, Willy to everyone else), a piece of rice lodged in her ear. She called this a “truly freaky thing” and not wanting to postpone her honeymoon, did not take the time to see a doctor. The rice caused a major ear infection, and when she did seek medical attention the instrument used to remove the rice kernel pierced the ear drum and resulted in further infection which caused total loss of hearing in that ear.

Billow was a wealthy Englishman in the cotton trade with business offices and homes in both London and Savannah. The couple settled in the Low House on Lafayette Square in Savannah for the first year of their marriage and then relocated to London. As Billow was a close friend of the Prince of Wales, they were quickly received in London society, Daisy’s brilliance as a hostess and infectious zest for life ensured they were well received. She was presented at court to Queen Victoria, an absolute must to secure her position in society, especially as she was American born. It took three hours to make their way through the various rooms at court to be presented to the Queen. Daisy got so tired of holding her bouquet that she placed it on the bustle of the lady in front of her leaving them there as they processed through the rooms, and the lady never noticed! She made great sport of poking fun of the British court’s smothering formality, and the Brit’s loved her for it, laughing along with her.

She easily made friends and was well liked, but she felt far too independent to truly fit into the mold of “fashionable boredom.” During this time period she became a notable sculptor. She expanded into woodcarving and carved a mantelpiece for one of her homes. She also discovered working in wrought iron and had her own foundry built and created her own blacksmith tools! She even created wrought iron gates for her home. The downside of her iron working was that her arms became so muscular, that she no longer could fit her Paris evening gowns!

In 1893 she had met Rudyard Kipling, whose wife Carrie was the granddaughter of Nellie Kinzie Gordon’s foster sister. Rudyard and Carrie became good friends of Daisy’s and she sometimes led him into mischief. She wrote home about one party where he was the guest of honor, “I was bored at one of the parties I was attending, and so pulled Kipling away from his friends and took him fishing. He kept complaining that we weren’t dressed for it (we were both in formal attire), but I never saw what difference our clothes made – it wasn’t as if they were the bait we were using!” Kipling had a bit of a different take on it:

“…there is a brook at the foot of our garden so that if you like (and Daisy did) you can go out after dinner in evening dress and try your luck for a fish. Also there is a high black bridge, under which trout lie, facing a banked stone wall some eight feet high. It was here, naturally, that Daisy got a fairly big one, and equally naturally it was I, in dinner costume, who lay on a long handled net taking Daisy’s commands while she maneuvered the fish into the net. We got him, between us, but it wasn’t my fault for I was too weak with laughter to do more than dab and scoop feebly in the directions she pointed out. And she had her own ways of driving her Ford in Scotland that chilled my blood and even impressed our daughter. But her own good angels looked after her even when she was on one wheel over a precipice; and there was nobody like her.”

During the Spanish American War, Daisy returned to the USA, and she and her mother established a convalescent hospital for soldiers returning from Cuba in Florida where her father was stationed. Her father, now commissioned as a general, served on the Puerto Rican Peace Commission. She returned to England at the end of the war, where she found that her already unhappy marriage was literally falling apart. Billow’s life in the fast lane of London society had become an issue in that he was drinking far too much as well as other vices, least of which was not his selfishness, which had led Billow to take delight in teasing Daisy knowing that her love for him left her virtually defenseless. What had begun no doubt innocently as a joke, developed over time into a pleasurable (for him) past time, he seemed to enjoy getting her into a dither over his safety, his well-being, his comfort, and took delight in knowing he could hurt her at will. And hurt her he did. Her absolutely loyal heart would not allow her to even mention to her family how he deliberately hurt her or how unhappy she was in her marriage. Eventually he began an affair with a young widow named Anna Bateman and by the summer of 1901 it had become well known. He taunted Daisy, hoping to push her into a divorce, even inviting Mrs. Bateman to Mealmore while Daisy was in residence and hosting a house party. Worse Mrs. Bateman began giving orders to the servants in Daisy’s presence as if she was hostess, and Billow was openly rude to her. Even then Daisy tired to protect him by refusing to leave until his sister Katy (whom she sent for) could come and take over as hostess to lend an air of propriety. She also sent for her sister Mabel who came and lent her moral support. Willy’s family and friends rightly blamed him for the troubles in his marriage and embraced Daisy with their love and friendship. Willy sank deeper into his drinking. In 1902 Daisy agreed to the divorce she had wished to avoid, but the complicated requirements of English law, and Willy’s unreasonable and erratic demands dragged out the negotiations and proceedings for years. Willy died in 1905 from complications of his excessive drinking before the divorce proceedings were complete, and Daisy found that he had left his entire estate to his mistress and her with only a small pension to be paid by the mistress. She wrote, “When my husband died, I found that he had willed his entire estate to another woman. No one was going to get away with that! Against the advice of my friends, I decided to contest the will, and eventually I won a $500,000 settlement.” This settlement also included all of her husband’s property in Georgia including the Low House on Lafayette Square. She decided to travel, spending part of the year in London and Scotland and the colder months in Savannah, as well as traveling across Europe and even to India. As her fiftieth birthday approached she became more dissatisfied with her life, and began looking for ever more ways to make her life feel useful.

It was during this time that she probably returned to doing home improvements and remodeled some of the furniture in her Georgia home. Jim Gannam wrote an article for Coastal Antiques and Art in July 2000 called “Daisy Made.” He highlights a large dinning room table that Daisy is attributed with cutting down and remodeling into an expandable multi-leaf table and several other pieces which now are housed at her birthplace home in Savannah. Unlike her earlier works these seem to show more impatience and a hurried approach to them. One chest on chest has carvings that Gannam says “is so out of character with the design of the piece that an observer might be tempted to think she was having a bit of a joke on later generations of her family.”

In 1911 she met the Boer War hero, Lieutenant General Sir Robert Baden-Powell (hero of the Siege of Mafeking.) Daisy and BP (as he was known to his friends) found they had many things in common including their love of sculpting. He introduced her to his growing scouting movement and his sister Agnes who was starting a companion Girl Guides movement. She soon founded a troop of Girl Guides near her estate in Glenlyon, Scotland. Wanting to find a way to better the lives of the girls, many of whom were unable to attend school and worked in unhealthy conditions in factories, she found a woman to teach her and the girls in her troop how to make cloth. The troop then sold the cloth in London and used the money to begin an egg business. The egg business became so successful that the girls no longer needed to work in the factories. Daisy subsequently started two more troops in London.

Several months later she returned to her native Savannah, and on March 12, 1912 called her cousin and said, “I’ve got something for the girls of Savannah, and all of America, and all the world, and we’re going to start it tonight!” Eighteen girls gathered at her house that night and thus began the Girl Scouts of America.

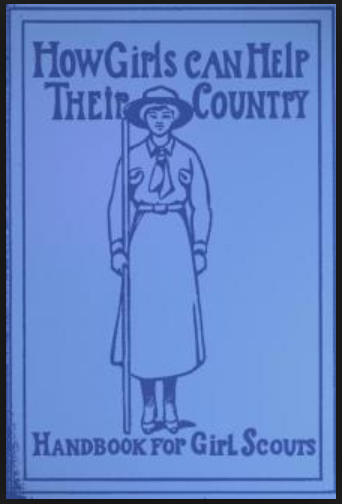

At 51 Daisy formed the first two troops of Girl Guides in Savannah registering her niece and namesake, Daisy Gordon, as the first member. She dedicated the next 15 years to building the organization which she renamed in 1913 Girl Scouts of America. She wrote the first handbook “How Girls Can Help Their Country” in 1913, and funded most of the organization personally during the early years, even selling her magnificent pearls for $8000.00 during WWI to ensure the organization could stay afloat financially. She made sure that girls of all backgrounds were given opportunities to develop self reliance and resourcefulness through outdoor activities.

Physically challenged girls were encouraged to participate at a time when most organizations excluded them. She also emphasized preparation in the arts, sciences, business, citizenship as well as the traditional home roles. She got a special permit from Savannah to teach the girls basketball. She wouldn’t take no for an answer and was known to use her hearing impairment and eccentricity to her advantage in getting her way when it came to getting things done for her scouts!. “When I returned to the States and wanted to start the Girl Scouts, I knew I needed some help. The first woman I approached tried to tell me she wasn’t interested. I pretended that my deafness prevented me from hearing her refusals. And told her, ‘Then that’s settled. I’ve told my girls you will take the meeting next Thursday.’ I never heard a word of argument from her again!” She used her sense of humor to get and keep interest in her movement, wearing hats trimmed with carrots and parsley at a fashionable luncheon she would remark, “Oh, is my trimming sad?” referring to the drooping vegetables. “I can’t afford to have this hat done over – I have to save all my money for my Girl Scouts. You know about the Scouts, don’t you?” She also pulled what her family called “stunts” just to keep things lively at otherwise boring committee meetings once standing on her head to show off the new uniform shoes! Daisy spent the last 15 years of her life and most of her personal fortune working to build the Girl Scouts with an organizational genius few could have guessed she possessed. She even recruited the First Lady Edith Wilson and Lou Hoover who later became First Lady and who proudly remained a scout for life and led the first Girl Scout cookie campaign. She maintained ties with the Girl Guides organization in Britain throughout WWI and helped to lay the foundation for the World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts.

Diagnosed with breast cancer in 1923, she kept the information to herself and continued to work non-stop at a feverish pace for her girls. That she managed to keep her condition and pain a secret stands as a testament to the strength of her will and character. Daisy died in Savannah on 17 January 1927, and she was buried in full Girl Scout Uniform with a telegram from the Girls Scout Council Executives tucked into the pocket that read, “You are not only the first Girl Scout, you are the best Girl Scout of them all.” Despite the hardships and disappointments that she faced, Daisy never lost her generous heart, her sense of humor, her courage or her determination. She has influenced us all in some fashion with her vision for girls, by the work and examples of the many outstanding former Girl Scouts who have shaped our nation, and through our mother’s, our sister’s and our own involvement in Girl Scouts.

Many have realized dreams because being a scout gave them self confidence to reach for them. Today you will find women of all walks of life who are former Girl Scouts from astronauts like Sally Ride, to Lois Juliber President of Colgate-Palmolive, to athletes like Jackie Joyner-Kersey, to fashion designer Vera Wang and even former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

The Girl Scout organization lists the following notable facts:

- On July 3, 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed a bill authorizing a stamp in honor of Juliette Gordon Low. The stamp was one of the few dedicated to women.

- During World War II, she had a “Liberty Ship” named in her honor. The S.S. Juliette Low built by the Southeastern Shipbuilding Corporation EC2-S-C1 Type Hull Number 51 MC# 2446, launched on 12 May 1944, she was scrapped in 1972.

- In 1954, in Georgia, the city of Savannah honored her by naming a school for her. A Juliette Low School also exists in Anaheim, California.

- On October 28, 1979, Juliette Low was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York.

- On December 2, 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill naming a new federal building in Savannah in honor of Juliette Low. It was the second federal building in history to be named after a woman.

- In 1992, a Georgia non-profit honored Juliette Low as one of the first Georgia Women of Achievement. A bust of Juliette Low is displayed in the State Capitol.

- In 2000, The Deaf World in Wax, a traveling exhibit, featured her as a famous deaf American.

- On October 14, 2005, Juliette Low’s life work was immortalized in a commemorative, bronze-and-granite medallion as part of a new national monument in Washington, D.C. The Extra Mile Points of Light Volunteer Pathway pays tribute to great Americans who built their dreams into movements that have created enduring change in America. The monument’s medallions, laid into sidewalks adjacent to the White House, form a one-mile walking path.

Sources:

Choate, Anne Hyde. Juliette Low and the Girl Scouts: the story of an American Woman, 1860-1927. Published for Girls Scouts Inc. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1928.

Pace, Mildred Mastin and Danny L. Miller, editors. Juliette Low. Jesse Stuart. Foundation, 1997.

Schultz, Gladys Denny and Daisy Gordon Lawrence. Lady from Savannah: The Life of Juliette Low. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1958.

Gordon Family Papers 1814-1936, Addition 1844-1849, 1853-1916, 635 b. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Library, Manuscripts Department & Southern Historical Collection. Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Low’s Papers in this collection: 1814-1936.

Girl Scouts of the USA www.girlscouts.org

Stuart Hall School Lynchburg, Virginia www.stuart-hall.org

Sherry Huggins, Spreading Like Kudzu http://wc.rootsweb.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=:2531483&id=I531691900